When I began writing seriously—not just for my own benefit to process my thoughts and feelings—I had many questions. In many ways, writing was a new and unfamiliar world, complete with its own language and vocabulary, rules and expectations, cultural mores and norms. I felt like a visitor, holding a passport but wanting citizenship.

I remembering asking my questions to any writer who was willing to listen. What kind of questions did I ask? Anything from the process of writing to how to grow in writing to what it means to be a Christian who writes. I also wondered, what does a writer do with the fact that many people have written on the same topic? If, for example, others have written on the topic of prayer or sanctification or suffering, how could I think I have anything to add to the conversation? After all, as the teacher noted, "What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecc. 1:9).

One of my favorite tutors on all things writing is C.S. Lewis. Christian Reflections is a collection of his essays and in his essay titled, “Christianity and Literature,” he describes the Christian writer in contrast to the unbelieving writer. “The unbeliever is always apt to make a kind of religion of his aesthetic experiences…He has to be ‘creative’; he has to obey a mystical amoral law called his artistic conscience.” Lewis describes modern literary criticism as exalting what is spontaneous, free of rules, innovative, and nonconforming.

But the believer in contrast is an imitator. "Our whole destiny seems to lie in the opposite direction, in being as little as possible ourselves, in acquiring a fragrance that is not our own but borrowed, in becoming clean mirrors filled with the image of a face that is not ours…the highest good of a creature must be creaturely—that is derivative or reflective.” As image bearers, created to image the One who created all things, our art is imitative art, meant to point to the Original Artist.

Further, Lewis notes, “Applying this principle to literature, in its greatest generality, we should get as the basis of all critical theory the maxim that an author should never conceive himself as bringing into existence beauty or wisdom which did not exist before, but simply and solely as trying to embody in terms of his own art some reflection of eternal Beauty and Wisdom.” This means we find our joy, not so much in building an identity as a creative, but in using our creativity to express the beauty and truth and wisdom of God.

While our art is imitative, it doesn’t mean it will all be the same. God created a diverse humanity with diverse voices and talents and experiences. This means that while we might write on the same topics, we write on those topics out of our God-given diverse gifts and experiences. You and I could both write on the topic of prayer and end up with two different pieces that while different, both point to the wonder and glory of the God who hears and answers our prayers.

The prophet was right, there isn’t anything new under the sun. But this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t write on a topic because other writers have already written on it. The question we ought to ask ourselves isn’t is what I’m writing new? but does what I write reflect the beauty and wisdom of God? Is it good? Does it bring him glory?

“So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:31).

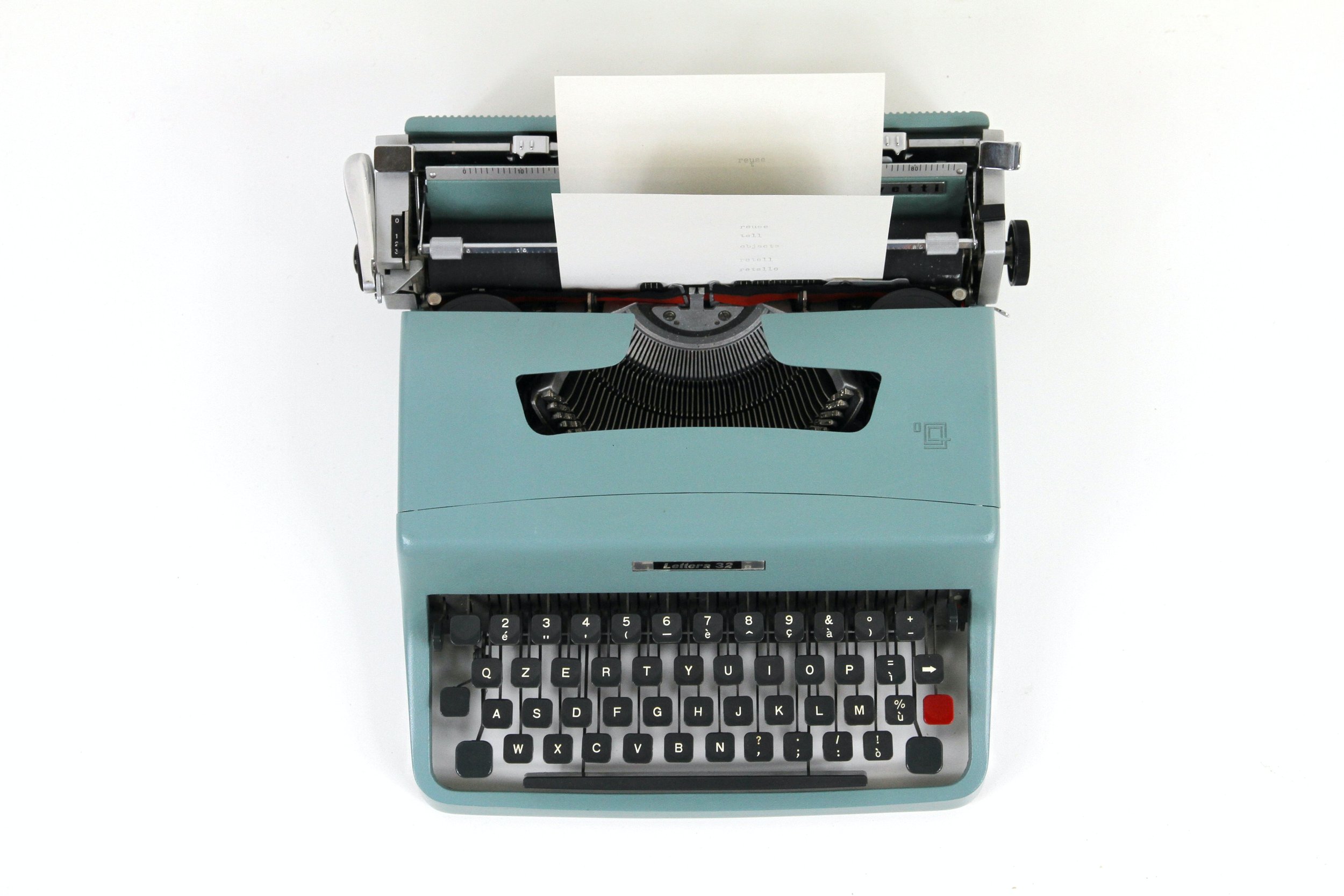

*Photo by Luca Onniboni on Unsplash